Biting Arthropods

of the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge (LSNWR)

Dan Kline, PhD

Over the next several months I plan to introduce you to various biting arthropods that you are likely to encounter within the boundaries of the LWNSR. Let me begin by defining what an arthropod is. Arthropoda is the largest phylum in the animal kingdom. About 84 per cent of all known animal species belong to this phylum. This phylum includes lobsters, crabs, spiders, mites, insects, centipedes and millipedes. The distinguishing feature of arthropods is the presence of a jointed skeletal covering. The body is usually segmented, and segments bear paired jointed appendages, from which the name arthropod (“jointed feet”) is derived. About one million species have been described, of which most are insects. I will be focusing on a sub-group, the biting arthropods, which include mostly insects (mosquitoes, biting midges, yellow flies, horse flies, stable flies, phlebotomine sandflies and blackflies) and acarines (ticks and chiggers).

Psorophora ciliata (Fabricius) and Psorophora ferox (Humboldt)

Mosquitoes

The featured biting arthropods for July belong to the insect order Diptera, family Culicidae. The family Culicidae is well known to all of us as mosquitoes.

There are approximately 80 species of mosquitoes known in the state of Florida and the number keeps increasing as new invasive species arrive. Worldwide, more than 3,500 species of mosquitoes have been identified, and each species has very particular biological requirements, such as the habitat in which the females’ lay eggs and the immature stages develop. There are four stages in a mosquito’s life cycle: egg, larva, pupa and adult.

Interesting information about a mosquito’s life cycle and suggestions for personal protection can be found in a pdf published by a team of entomologists from UF IFAS Florida Medical Entomology Lab (FMEL) entitled “Integrated Pest Management for Mosquito Reduction around Homes and Neighborhoods” (https:edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN104500.pdf).

There are approximately 80 species of mosquitoes known in the state of Florida and the number keeps increasing as new invasive species arrive. Worldwide, more than 3,500 species of mosquitoes have been identified, and each species has very particular biological requirements, such as the habitat in which the females’ lay eggs and the immature stages develop. There are four stages in a mosquito’s life cycle: egg, larva, pupa and adult.

Interesting information about a mosquito’s life cycle and suggestions for personal protection can be found in a pdf published by a team of entomologists from UF IFAS Florida Medical Entomology Lab (FMEL) entitled “Integrated Pest Management for Mosquito Reduction around Homes and Neighborhoods” (https:edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN104500.pdf).

Eggs – Permanent Water and Floodwater

In this publication they point out that there are various types of eggs, which vary in size and shape depending on the species. Some mosquito species have eggs with floats on the side, and some eggs are covered with small bumps. Eggs that are deposited on the water surface, called permanent water eggs, cannot withstand drying out and usually hatch within a day or two. Eggs that are deposited on a moist substrate, called floodwater eggs, require a period of drying out, and then will hatch when covered with water.

In this publication they point out that there are various types of eggs, which vary in size and shape depending on the species. Some mosquito species have eggs with floats on the side, and some eggs are covered with small bumps. Eggs that are deposited on the water surface, called permanent water eggs, cannot withstand drying out and usually hatch within a day or two. Eggs that are deposited on a moist substrate, called floodwater eggs, require a period of drying out, and then will hatch when covered with water.

Larvae -- Wrigglers

All mosquito larvae are aquatic, and the larvae of each species are adapted to a specific aquatic habitat. Larvae of most species come to the surface to breathe through “breathing tube” known as a siphon. One type of mosquito, Anopheles, does not have a siphon and breathes through specialized pores, known as spiracles, as lays horizontally to the water’s surface. Mosquito larvae cannot survive out of water. Mosquito larvae are called “wrigglers” because of the way they swim through the water, using an s-shaped motion. The larval stage can last from several days to several months depending on the water temperature and the mosquito species. Larvae will feed on algae, bacteria, copepods, yeast, other microorganisms and organic matter in the water.

All mosquito larvae are aquatic, and the larvae of each species are adapted to a specific aquatic habitat. Larvae of most species come to the surface to breathe through “breathing tube” known as a siphon. One type of mosquito, Anopheles, does not have a siphon and breathes through specialized pores, known as spiracles, as lays horizontally to the water’s surface. Mosquito larvae cannot survive out of water. Mosquito larvae are called “wrigglers” because of the way they swim through the water, using an s-shaped motion. The larval stage can last from several days to several months depending on the water temperature and the mosquito species. Larvae will feed on algae, bacteria, copepods, yeast, other microorganisms and organic matter in the water.

Pupae -- Tumblers

Pupae are also aquatic and cannot survive for very long out of water. They have to come to the water surface to breathe through specialized structures known as “trumpets”. Pupae are called “tumblers” because of the way they dive down and tumble through the water when disturbed. Adults do not feed; this is a transitional stage, which usually lasts two to three days.

Pupae are also aquatic and cannot survive for very long out of water. They have to come to the water surface to breathe through specialized structures known as “trumpets”. Pupae are called “tumblers” because of the way they dive down and tumble through the water when disturbed. Adults do not feed; this is a transitional stage, which usually lasts two to three days.

Adulthood

The last stage is the adult. In this stage they mate, find blood sources (only the females take blood), lay eggs, find resting places and try to escape predators and the efforts of humans to manage their populations.

The last stage is the adult. In this stage they mate, find blood sources (only the females take blood), lay eggs, find resting places and try to escape predators and the efforts of humans to manage their populations.

July’s Featured Species

This month two species of floodwater mosquitoes are featured due to the recent abundant rainfall the LSNWR has experienced. If you have been walking the trails since early July, you probably have been attacked by swarms of mosquitoes. My biological technician and I were clearing some fallen trees on both the Dixie and Levy sides of the Refuge this past week, the second week in July 2023, and were viciously attacked by swarms of Psorophora ciliata and Ps. ferox. As is the case with most biting Diptera, only the females bite, and thus the swarms were composed only of females. Most species need blood to produce and mature their eggs and these two floodwater species are no exception.

This month two species of floodwater mosquitoes are featured due to the recent abundant rainfall the LSNWR has experienced. If you have been walking the trails since early July, you probably have been attacked by swarms of mosquitoes. My biological technician and I were clearing some fallen trees on both the Dixie and Levy sides of the Refuge this past week, the second week in July 2023, and were viciously attacked by swarms of Psorophora ciliata and Ps. ferox. As is the case with most biting Diptera, only the females bite, and thus the swarms were composed only of females. Most species need blood to produce and mature their eggs and these two floodwater species are no exception.

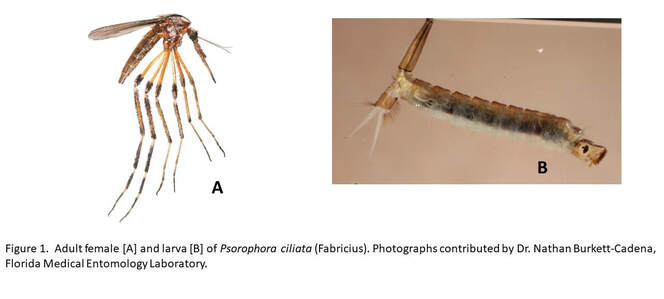

Psorophora ciliata also known as the gallinipper, is the largest of the biting mosquitoes in our area. It has a body length of about 18 mm (nearly three quarters of an inch). The body and legs of this species are quite stout and have a yellowish hue (Figure 1A). Patches of black, white, and golden scales adorn the body. The legs have tufts of dark, erect scales on the femur and tibia, resulting in a shaggy appearance. The hind tarsi (=”foot”) have broad pale bands at the base of each segment. Psorophora ciliata feed on mammals, including deer, rabbits, armadillos. Livestock and humans. Although their bite can be quite painful, they are not known to transmit any disease agents to humans. They can be quite pestiferous and persistent biters in places where they are abundant, particularly in coastal areas. Larvae of Psorophora ciliata are quite large (Figure 1B). Larvae are most commonly encountered in temporary rainwater pools exposed to full sun. They are predaceous and develop rapidly, completing development in as little as 3-5 days.

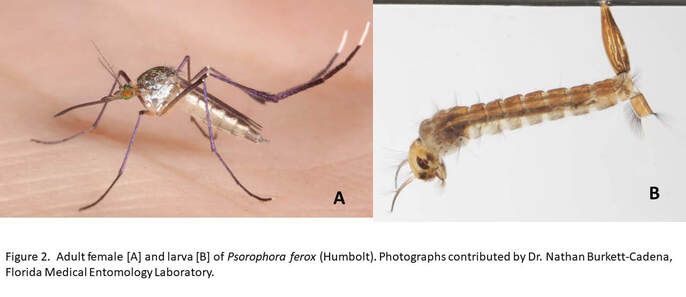

Psorophora ferox adults are medium sized, colorful mosquitoes (Figure 2A). Their legs are iridescent purple and the last segments of the hind legs are bright white, giving the appearance of white socks. Their eyes appear bright green in life. Females feed on mammals, especially deer, rabbits, livestock, and humans. They can be quite bothersome, especially in late afternoon in shaded areas and in dense woods. This species is not known to be important in the transmission of any human pathogens in the United States. Larvae are medium sized and usually brownish (Figure 2B). Setae (hairs) of the head are quite long, usually much longer than the head, and often black. The siphon is large and appears slightly swollen just beyond its base. Larvae occur in woodland pools and overflow puddles along streams following rains.

Personal Protection

When hiking, fishing, hunting, or performing other activities on the Refuge, if mosquitoes are present, Personal Protection is important. This can be accomplished by wearing clothes that covers most of your skin. Certain products containing permethrin are recommended for use on clothing. Permethrin is registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for this use. Permethrin is highly effective as an insecticide and as a contact repellent. Permethrin-treated clothing repels and kills ticks, mosquitoes, and other biting arthropods and retains this effect after repeated laundering. The permethrin insecticide should be used following the label instructions. Never apply it to the bare skin. Some commercially treated clothing products are available. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the use of certain products containing active ingredients that have been registered by the EPA for use as repellents applied to skin and clothing. Two examples are DEET and picaridin products. EPA and CDC provide recommendations for the use of registered repellents. Several important recommendations are: apply repellents only to exposed skin and/or clothing (as directed on the product label); do not use repellents under clothing; never use repellents over cuts, wounds or irritated skin; do not apply to eyes or mouth, and apply sparingly around ears; when using sprays, do not spray directly on the face, rather spray on hands first and then apply to face.

When hiking, fishing, hunting, or performing other activities on the Refuge, if mosquitoes are present, Personal Protection is important. This can be accomplished by wearing clothes that covers most of your skin. Certain products containing permethrin are recommended for use on clothing. Permethrin is registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for this use. Permethrin is highly effective as an insecticide and as a contact repellent. Permethrin-treated clothing repels and kills ticks, mosquitoes, and other biting arthropods and retains this effect after repeated laundering. The permethrin insecticide should be used following the label instructions. Never apply it to the bare skin. Some commercially treated clothing products are available. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the use of certain products containing active ingredients that have been registered by the EPA for use as repellents applied to skin and clothing. Two examples are DEET and picaridin products. EPA and CDC provide recommendations for the use of registered repellents. Several important recommendations are: apply repellents only to exposed skin and/or clothing (as directed on the product label); do not use repellents under clothing; never use repellents over cuts, wounds or irritated skin; do not apply to eyes or mouth, and apply sparingly around ears; when using sprays, do not spray directly on the face, rather spray on hands first and then apply to face.

Chrysops vittatus Weidemann and

C. celatus Pechuman

These biting arthropods belong to the insect order Diptera, family Tabanidae, subfamily Chrysopinae, genus Chrysops. The family Tabanidae is commonly referred to as horse and deer flies. Tabanidae are of economic importance due to the blood-feeding habits of the females of most species. These insects have been implicated in the transmission of diseases of veterinary and medical importance (biological transmission of erlichiosis of deer and elk and mechanical transmission of anaplasmosis, anthrax, vesicular stomatitis and hog cholera). Some species are also notorious human pests and may result in negative economic impact by limiting the use of recreation areas for fishing, hunting, and leisure.

Host-Seeking Deer Flies Are Abundant on the Lower Suwannee NWR in May and June

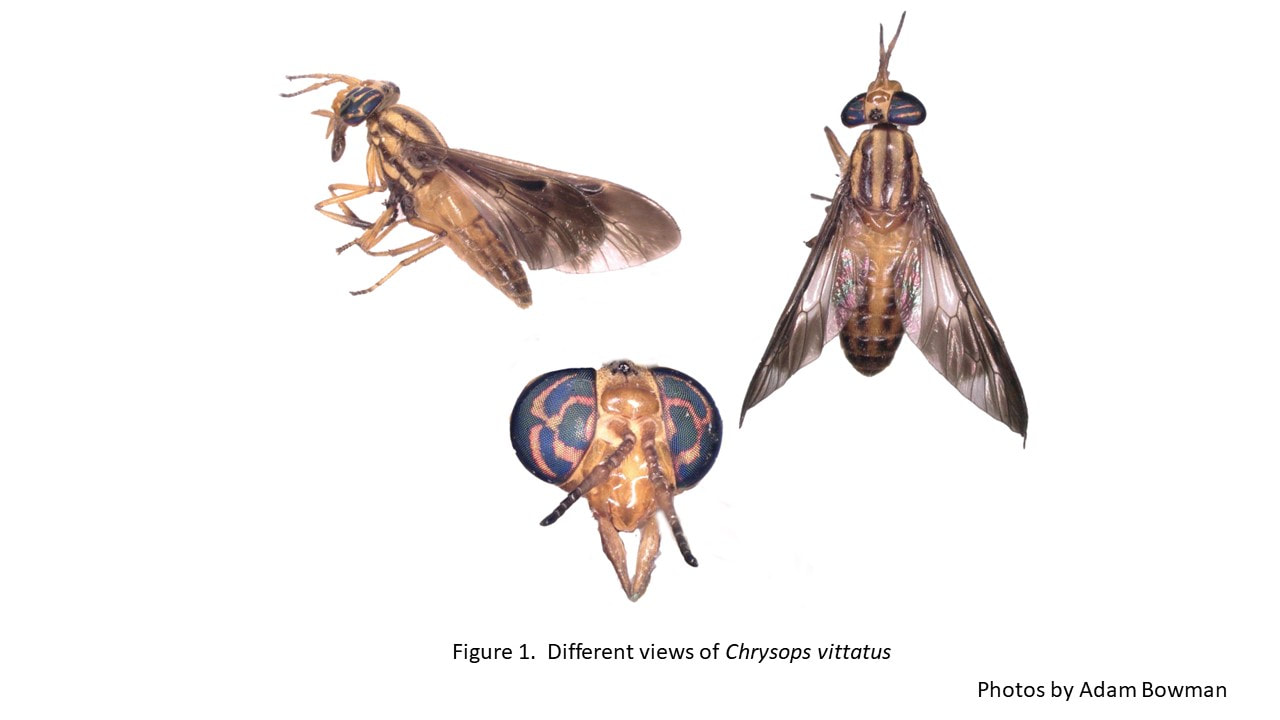

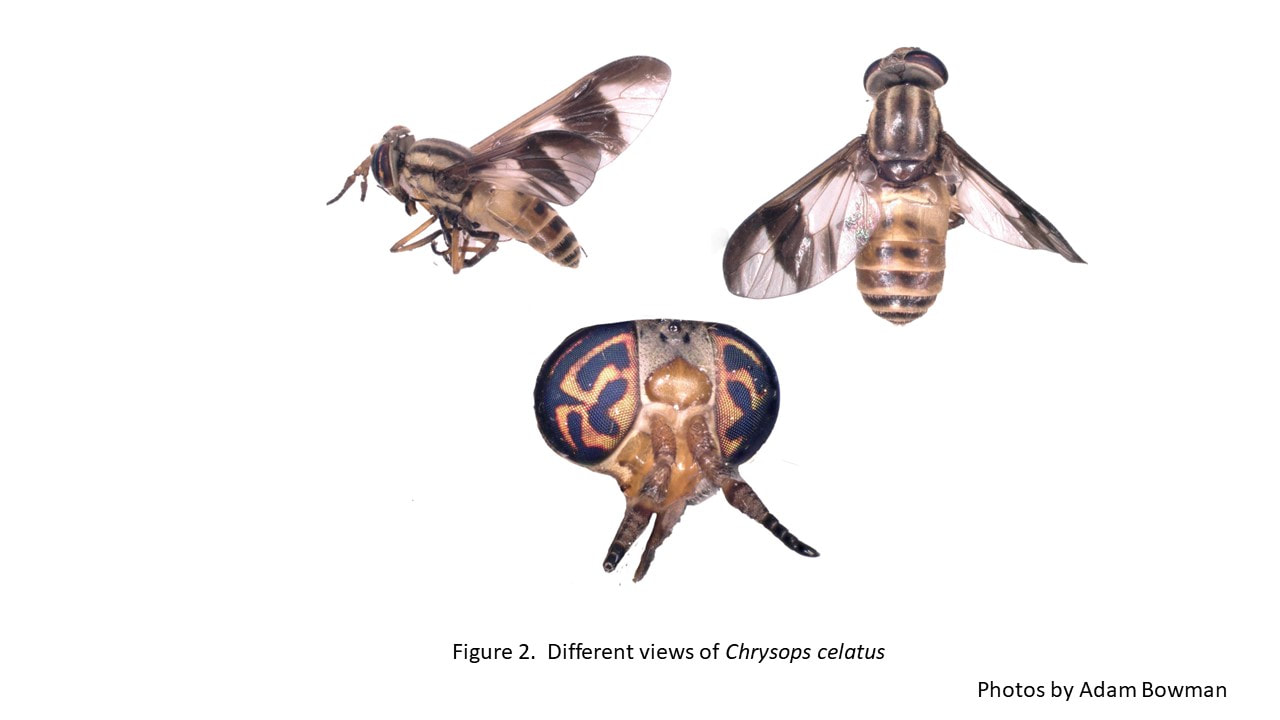

Featured this month are host-seeking deer flies, sometimes locally referred to as yellow flies, which can often become a serious nuisance and large pestiferous populations can certainly discourage enjoyment of outdoor activities. Two species, Chrysops vittatus Weidemann (Figure 1) and C. celatus Pechuman (Figure 2), are seasonally abundant (May-June) within the LSNWR. These insects persistently attack the head region of people. Their host-seeking behavior is not only discomforting, but the bite can be painful and allergic reactions may occur.

Catching Deer Flies to Study is Harder than You Might Expect

We have been conducting population dynamics studies on these two species at the LSNWR for over ten years. These two species have been difficult to lure into traps. Therefore, population monitoring has been a challenge. Sampling is usually labor-intensive, often requiring capture by aerial net around a moving human subject. The standard method consists of continually swinging the net in figure “8” sweeps that start at ankles and end above the head while walking.

Recently, we observed that these two species are attracted to the mirrors of a moving vehicle. Thus, we developed a method where these deer flies are captured as they are attracted to the mirrors, using a power aspirator (Figure 3). The vehicle must not exceed a speed of 5 mph. Our studies have shown great fluctuations in population abundance from year to year. The past two years populations have been comparatively very low.

Trails Where Deer Flies are Perennially Abundant in May and June

Several trails have been observed to have large populations almost every year. These include Beaver Dam Road, Weeks Landing, Yellow Jacket on the Dixie side, and trails behind gates 14, 18, 19, 20 and 34 on the Levy side; populations can also be abundant on the River Trail.

To Repel or To Attract? That is the Question.

Repellents applied to exposed skin have not been very effective against these pests, especially for extended periods of time. Insecticides applied to, or impregnated in clothing have been reported to provide some repellency in field situations. Adhesive patches (Figure 4), affixed to headwear, have been evaluated and found as an effective way to reduce biting deer fly pressure on an individual basis. These adhesive patches have successfully captured both species of deer flies, which are attracted to people actively walking, jogging or bicycle riding along the trails. The deer flies orient to the back of a moving human’s head, probably due to a plume of carbon dioxide being expired. Published studies have reported that patches affixed to the back of caps captured significantly more flies than those affixed to the front.

Culicoides mississippiensis Hoffman

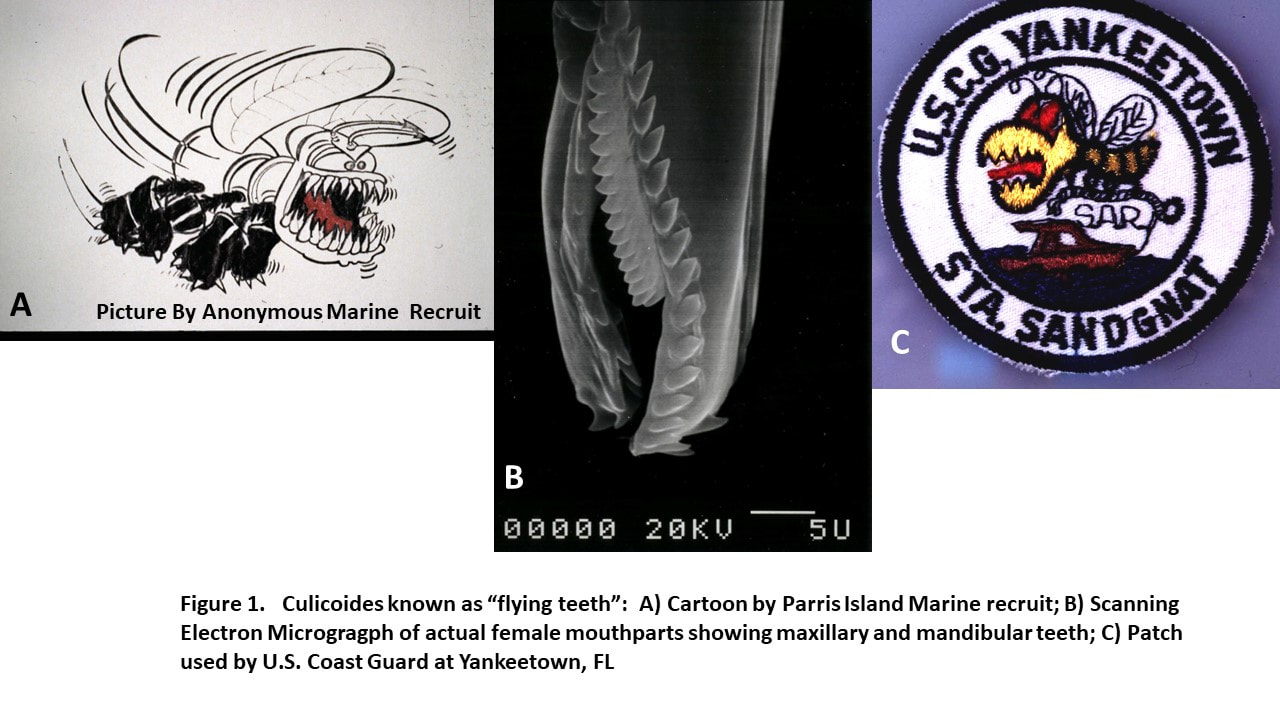

This were the first of our featured species and was posted in April 2023. It belongs to the class Insecta, order Diptera (2-winged flies) and family Ceratopogonidae, genus Culicoides. Collectively, members of this genus are most known as biting midges. Other common names are no-see-ums, sandflies, biting gnats, punkies and my favorite “flying teeth”. This is an apt description of the pain the females inflict.

Figure 1A depicts a cartoon drawn by and given to me through a Preventive Medicine officer by a U.S. marine recruit undergoing basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina. Figure 1B shows a scanning electron micrograph of the actual mouthparts of an adult female. Figure 1C is a patch worn by some Coast Guard personnel stationed at Yankeetown. There are 47 species of Culicoides known to occur in Florida. The exact number of species occurring within the boundaries of the LSNWR has not yet been determined. Except for mosquitoes, and this may be debatable, no other insects cause more human discomfort to visitors and workers of the LSNWR than several species of biting midges. Adults are extremely small (ca. 1/8 “long). They have a distinct wing pattern which is used to distinguish species. Only females take blood, which is usually required to mature a batch of eggs. Each female will mature 2-4 batches of eggs in her lifetime. A separate blood meal is required for each batch of eggs. The life cycle consists of four stages, egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Females lay their eggs on mud. The eggs are very small (0.25 mm); they hatch in 3-5 days. Larvae go through 4 instars (1/16 -1/8” long), they are creamy white and eel-like in appearance; normally develop in the mud and are predaceous on other small organisms. Development time is dependent on the temperature and season. Pupae (1/8” long) also occur in the mud and generally complete development in 3-5 days. Male adults emerge first, usually 24 hr before the females. Initially, both sexes feed on nectar. Mating often occurs in swarms. The males form swarms above shrubs and females enter the swarms and mating occurs. Usually, after 3-4 days, the females will seek their first blood meal; there are exceptions.

|

While we haven’t yet identified all the species of biting midges occurring within the LSNWR, there are two species (C. furens and C. mississippiensis) that cause the most discomfort to refuge visitors. Therefore, this month’s featured species is C. mississippiensis. This species breeds in the mud of tidal saltmarshes with vegetation marked by black needle rush (Juncus roemerianus) fringed by Spartina alterniflora cordgrass. Adults are gray and brown with distinct wing markings (Figure 2).

|

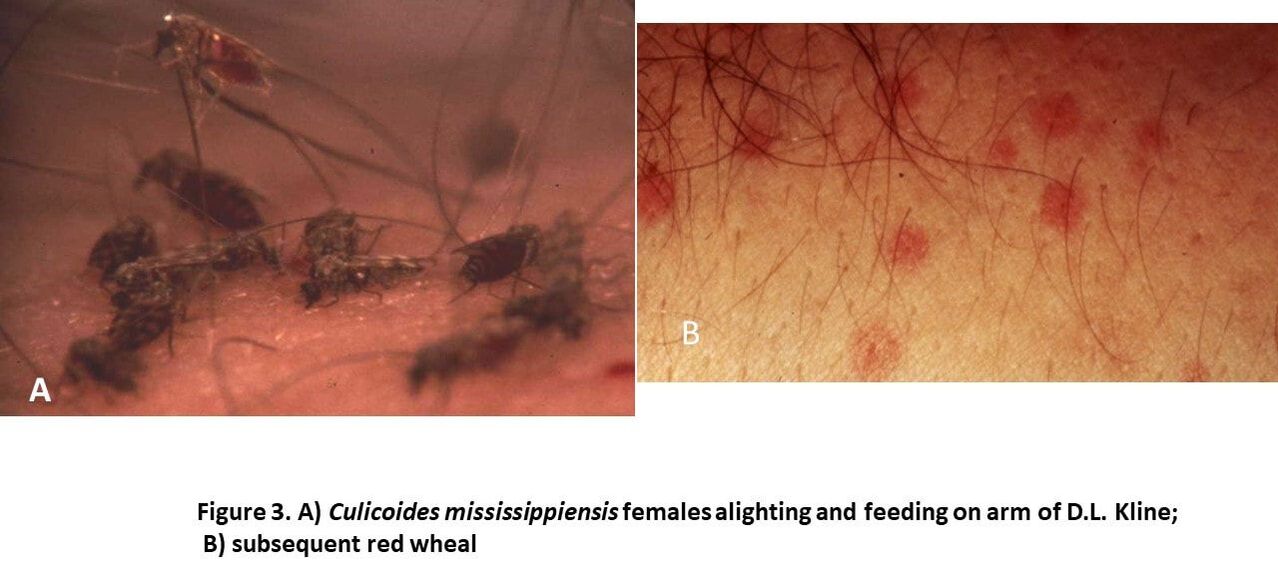

Females are fierce biters and when present cause much annoyance. Females do not bite immediately when alighting but begin ‘crawling about’ in search of vulnerable spots (Figure 3A). The wound produces an intense burning sensation and a small red wheal (Figure 3B), which usually appears in a short time and will persist in most individuals for about 24 hr.

Culicoides mississippiensis occurs throughout the year with very prominent peaks in March-May and October-November. Upon emergence both sexes feed on nectar from flowering plants. Ilex vomitoria, which flowers in early spring and is very abundant at several locations (e.g., along the Dennis Creek Trail and at Shell Mound boat ramp) within LSNWR is one of their favorite nectar sources. We have collected large numbers of both sexes from this plant when it is in the flowering stage. The life cycle of this species differs from most Culicoides species in that the females do not need a blood meal to produce their first batch of eggs. They have enough nutrients carried over from their larva stage that they can produce the first batch of eggs without a blood meal. This process is known as autogeny. All subsequent batches of eggs require a blood meal. Biting activity occurs throughout the day but is most active in late afternoon/early evening. They are most annoying when there is no breeze.

There is very little that can be done to protect yourself from their biting activity. Topical repellents work to some degree, but their effectiveness is short lived. Some individuals like to wear long sleeves and pants with a fine mesh head net. When using the head net make sure it is secured in a manner which excludes the blood seeking females from getting inside the net or else the face will become an excellent feeding ground!

Friends of the Lower Suwannee & Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuges

P. O. Box 532 Cedar Key, FL 32625 [email protected] We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. |

|