Recreational Opportunities

Walking

- Shell Mound Archaeological Trail guide (see below)

- Dennis Creek Trail Guide

- Camping is prohibited on the Refuge but welcome at the nearby Levy County Shell Mound Campground

- Fishing on the Refuge falls entirely under the State of Florida's fishing regulations

Follow us for Junior Ranger answers!

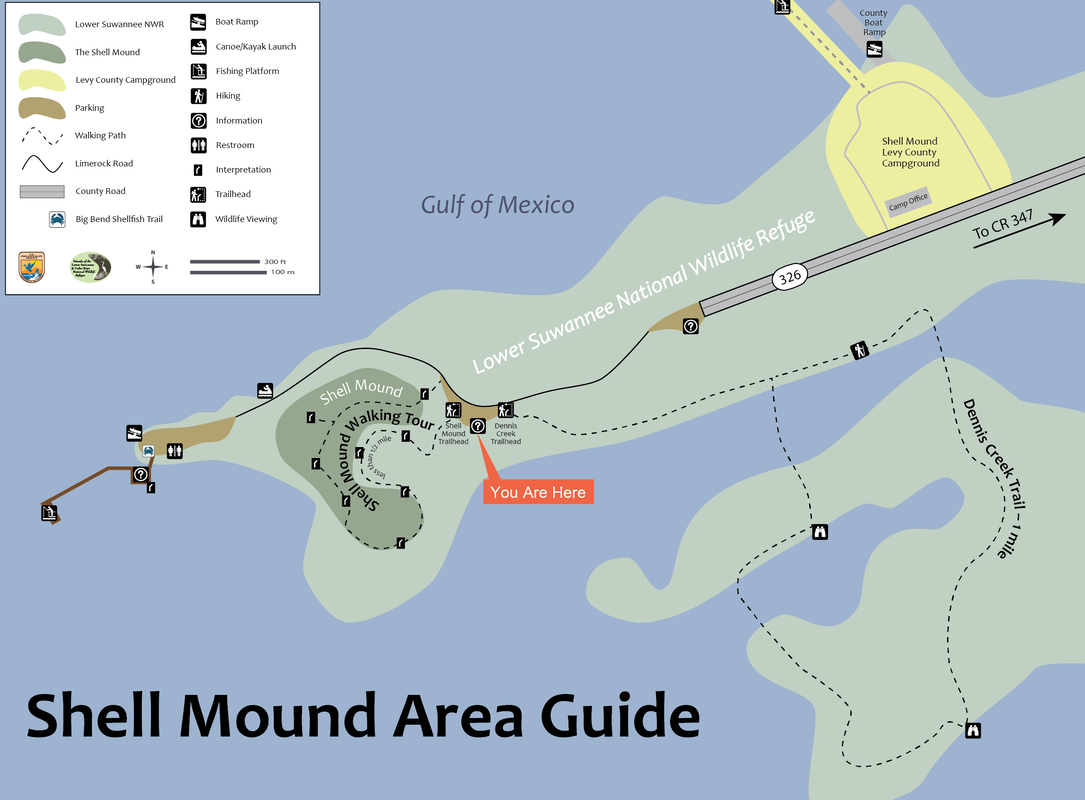

Shell Mound, on the Levy county side of the Lower Suwannee NWR, is located on Highway 326 about eight miles from the town of Cedar Key.

Shell Mound attracts thousands of visitors each year. Some come to fish from the pier. Others put in their kayaks and small boats at the tide-dependent launch area. Some walk the one-mile Dennis Creek Trail through marshes and hammocks.

For many, the highlight of the visit is the walk on the self-guided, less than a half-mile Shell Mound archaeological trail.

Despite its unassuming name, Shell Mound (8LV42 to archaeologists), is a large shell-bearing archaeological site that was once the location of special gatherings for Native American groups across the broader region.

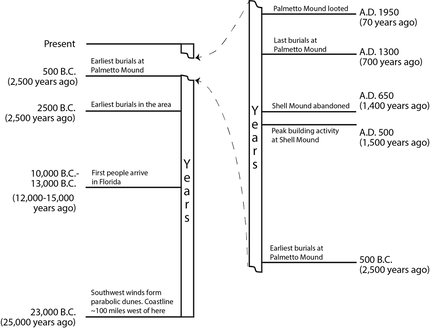

The site rose to prominence as a ritual center at about A.D. 400 and continued through A.D. 650. Archaeologists refer to places such as this as “civic-ceremonial centers,” locations of both residence and ritual activity. Like other civic-ceremonial centers in the region, Shell Mound drew its significance from a nearby cemetery, the hallowed ground of ancestors from far and wide.

The site features mounds of marine shell (predominately oyster) measuring about 23 feet high surrounding a large central plaza. Excavations by archaeologists from the University of Florida have discovered the remains of large feasts that took place in the summer–likely celebrating the Summer Solstice–the longest day of the year.

Our Friends group gathers on most Summer and Winter Solstices, rain or shine . . . mostly rain, its seems, to mark the importance of Shell Mound with special talks and tours. Read blog posts about Friends gatherings.

Shell Mound attracts thousands of visitors each year. Some come to fish from the pier. Others put in their kayaks and small boats at the tide-dependent launch area. Some walk the one-mile Dennis Creek Trail through marshes and hammocks.

For many, the highlight of the visit is the walk on the self-guided, less than a half-mile Shell Mound archaeological trail.

Despite its unassuming name, Shell Mound (8LV42 to archaeologists), is a large shell-bearing archaeological site that was once the location of special gatherings for Native American groups across the broader region.

The site rose to prominence as a ritual center at about A.D. 400 and continued through A.D. 650. Archaeologists refer to places such as this as “civic-ceremonial centers,” locations of both residence and ritual activity. Like other civic-ceremonial centers in the region, Shell Mound drew its significance from a nearby cemetery, the hallowed ground of ancestors from far and wide.

The site features mounds of marine shell (predominately oyster) measuring about 23 feet high surrounding a large central plaza. Excavations by archaeologists from the University of Florida have discovered the remains of large feasts that took place in the summer–likely celebrating the Summer Solstice–the longest day of the year.

Our Friends group gathers on most Summer and Winter Solstices, rain or shine . . . mostly rain, its seems, to mark the importance of Shell Mound with special talks and tours. Read blog posts about Friends gatherings.

Each panel below is a stop on the Shell Mound Trail

Where's the Mound?

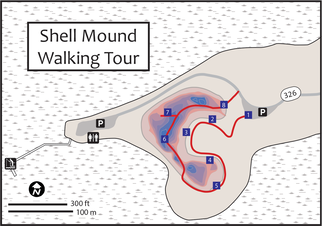

Shell Mound is a semicircular ridge of shell and earth that was built by Native Americans on the arm of an ancient sand dune. The red and blue shading on the map above marks the contours of the mound, which is composed of about 1.2 billion oyster shells. Your tour begins by entering the site through the space enclosed by the ridge. From inside this enclosed space you will see how Shell Mound resembles an amphitheater. Much of the shape and size of the ridges is the work of people, but beneath the shell along the north ridge is the sand of an ancient dune. You will reach the apex of Shell Mound from the south ridge, where you will enjoy commanding views of both the enclosed space to the east and Gulf waters to the west. All from a height of about 23 feet (7 meters).

Shell Mound is a semicircular ridge of shell and earth that was built by Native Americans on the arm of an ancient sand dune. The red and blue shading on the map above marks the contours of the mound, which is composed of about 1.2 billion oyster shells. Your tour begins by entering the site through the space enclosed by the ridge. From inside this enclosed space you will see how Shell Mound resembles an amphitheater. Much of the shape and size of the ridges is the work of people, but beneath the shell along the north ridge is the sand of an ancient dune. You will reach the apex of Shell Mound from the south ridge, where you will enjoy commanding views of both the enclosed space to the east and Gulf waters to the west. All from a height of about 23 feet (7 meters).

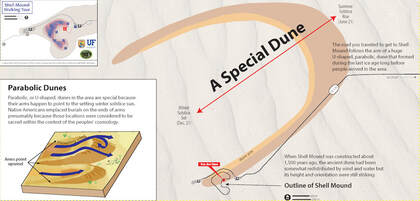

A Special Dune

The road you traveled to get to Shell Mound follows the arm of a huge U-shaped, parabolic, dune that formed during the last ice age long before people arrived in the area. When Shell Mound was constructed about 1,500 years ago, the ancient dune had been somewhat redistributed by wind and water but its height and orientation were still striking.

Parabolic, or U-shaped, dunes in the area are special because their arms happen to point to the setting winter solstice sun. Native Americans emplaced burials on the ends of arms presumably because those locations were considered to be sacred within the context of the peoples' cosmology.

The road you traveled to get to Shell Mound follows the arm of a huge U-shaped, parabolic, dune that formed during the last ice age long before people arrived in the area. When Shell Mound was constructed about 1,500 years ago, the ancient dune had been somewhat redistributed by wind and water but its height and orientation were still striking.

Parabolic, or U-shaped, dunes in the area are special because their arms happen to point to the setting winter solstice sun. Native Americans emplaced burials on the ends of arms presumably because those locations were considered to be sacred within the context of the peoples' cosmology.

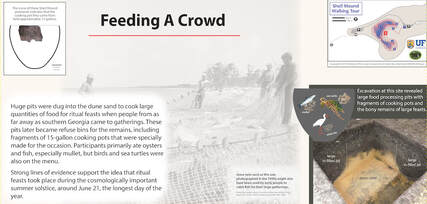

Feeding a Crowd

Huge pits were dug into the dune sand to cook large quantities of food for ritual feasts when people from as far away as southern Georgia came to gatherings. These pits later became refuse bins for the remains, including fragments of 15-gallon cooking pots that were specially made for the occasion. Participants primarily ate oysters and fish, especially mullet, but birds and sea turtles were also on the menu.

Strong lines of evidence support the idea that ritual feasts took place during the cosmologically important summer solstice, around June 21, the longest day of the year.

More about summer solstice feasts at Shell Mound.

Huge pits were dug into the dune sand to cook large quantities of food for ritual feasts when people from as far away as southern Georgia came to gatherings. These pits later became refuse bins for the remains, including fragments of 15-gallon cooking pots that were specially made for the occasion. Participants primarily ate oysters and fish, especially mullet, but birds and sea turtles were also on the menu.

Strong lines of evidence support the idea that ritual feasts took place during the cosmologically important summer solstice, around June 21, the longest day of the year.

More about summer solstice feasts at Shell Mound.

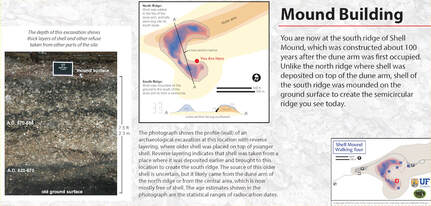

Mound Building

You are now at the south ridge of Shell Mound, which was constructed about 100 years after the dune arm was first occupied. Unlike the north ridge where shell was deposited on top of the dune arm, shell of the south ridge was mounded on the ground surface to create the semicircular ridge you see today.

The photograph shows the profile (wall) of an archaeological excavation at this location with reverse layering, where older shell was placed on top of younger shell. Reverse layering indicates that shell was taken from a place where it was deposited earlier and brought to this location to create the south ridge. The source of this older shell is uncertain, but it likely came from the dune arm of the north ridge or from the central area, which is now mostly free of shell. The age estimates shown in the photograph are the statistical ranges of radiocarbon dates.

You are now at the south ridge of Shell Mound, which was constructed about 100 years after the dune arm was first occupied. Unlike the north ridge where shell was deposited on top of the dune arm, shell of the south ridge was mounded on the ground surface to create the semicircular ridge you see today.

The photograph shows the profile (wall) of an archaeological excavation at this location with reverse layering, where older shell was placed on top of younger shell. Reverse layering indicates that shell was taken from a place where it was deposited earlier and brought to this location to create the south ridge. The source of this older shell is uncertain, but it likely came from the dune arm of the north ridge or from the central area, which is now mostly free of shell. The age estimates shown in the photograph are the statistical ranges of radiocarbon dates.

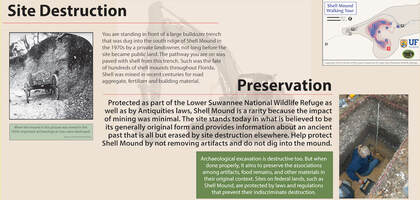

Site Destruction

You are standing in front of a large bulldozer trench that was dug into the south ridge of Shell Mound in the 1970s by a private landowner, not long before the site became public land. The pathway you are on was paved with shell from this trench. Such was the fate of hundreds of shell mounds throughout Florida. Shell was mined in recent centuries for road aggregate, fertilizer and building material.

Preservation

Protected as part of the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge as well as by Antiquities laws, Shell Mound is a rarity because the impact of mining was minimal. The site stands today in what is believed to be its generally original form and provides information about an ancient past that is all but erased by site destruction elsewhere. Help protect Shell Mound by not removing artifacts and do not dig into the mound.

You are standing in front of a large bulldozer trench that was dug into the south ridge of Shell Mound in the 1970s by a private landowner, not long before the site became public land. The pathway you are on was paved with shell from this trench. Such was the fate of hundreds of shell mounds throughout Florida. Shell was mined in recent centuries for road aggregate, fertilizer and building material.

Preservation

Protected as part of the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge as well as by Antiquities laws, Shell Mound is a rarity because the impact of mining was minimal. The site stands today in what is believed to be its generally original form and provides information about an ancient past that is all but erased by site destruction elsewhere. Help protect Shell Mound by not removing artifacts and do not dig into the mound.

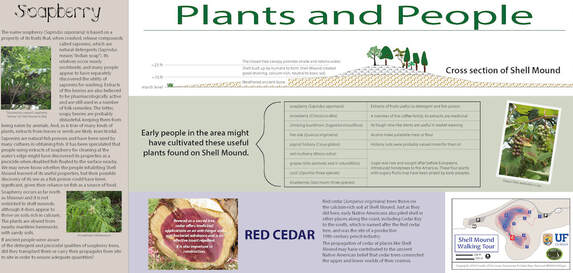

Plants and People

Early people in the area might have cultivated these useful plants found on Shell Mound.

Early people in the area might have cultivated these useful plants found on Shell Mound.

Plant |

Use |

soapberry (Sapindus saponaria) |

Extracts of fruits useful as detergent and fish poison |

snowberry (Chiococca alba) |

A member of the coffee family, its extracts are medicinal |

climbing buckthorn (Sageretia minutiflora) |

Its tough vine-like stems are useful in basket weaving |

live oak (Quercus virginiana) |

Acorns make palatable meal or our |

pignut hickory (Carya glabra) |

Hickory nuts were probably valued more for their oil |

red mulberry (Morus rubra) grapes (Vitis aestivalis and V. rotundifolia) cacti (Opuntia: three species) blueberries (Vaccinium: three species) |

Sugar was rare and sought after before Europeans introduced honeybees to the Americas. These four plants with sugary fruits may have been prized by early peoples. |

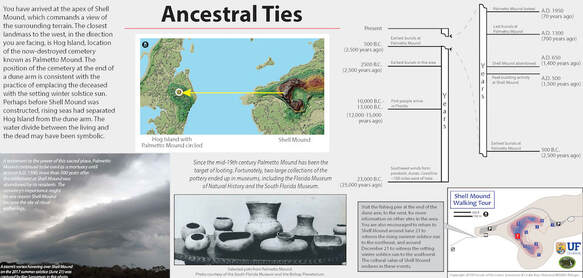

Ancestral Ties

You have arrived at the apex of Shell Mound, which commands a view of the surrounding terrain. The closest landmass to the west, in the direction you are facing, is Hog Island, location of the now-destroyed cemetery known as Palmetto Mound. The position of the cemetery at the end of a dune arm is consistent with the practice of emplacing the deceased with the setting winter solstice sun. Perhaps before Shell Mound was constructed, rising seas had separated Hog Island from the dune arm. The water divide between the living and the dead may have been symbolic.

You have arrived at the apex of Shell Mound, which commands a view of the surrounding terrain. The closest landmass to the west, in the direction you are facing, is Hog Island, location of the now-destroyed cemetery known as Palmetto Mound. The position of the cemetery at the end of a dune arm is consistent with the practice of emplacing the deceased with the setting winter solstice sun. Perhaps before Shell Mound was constructed, rising seas had separated Hog Island from the dune arm. The water divide between the living and the dead may have been symbolic.

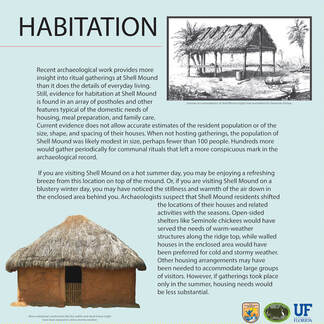

Habitation

Recent archaeological work provides more insight into ritual gatherings at Shell Mound than it does the details of everyday living. Still, evidence for habitation at Shell Mound is found in an array of postholes and other features typical of the domestic needs of housing, meal preparation, and family care. Current evidence does not allow accurate estimates of the resident population or of the size, shape, and spacing of their houses. When not hosting gatherings, the population of Shell Mound was likely modest in size, perhaps fewer than 100 people. Hundreds more would gather periodically for communal rituals that left a more conspicuous mark in the archaeological record. If you are visiting Shell Mound on a hot summer day, you may be enjoying a refreshing breeze from this location on top of the mound. Or, if you are visiting Shell Mound on a blustery winter day, you may have noticed the stillness and warmth of the air down in the enclosed area behind you. Archaeologists suspect that Shell Mound residents shifted the locations of their houses and related activities with the seasons. Open-sided shelters like Seminole chickees would have served the needs of warm-weather structures along the ridge top, while walled houses in the enclosed area would have been preferred for cold and stormy weather. Other housing arrangements may have been needed to accommodate large groups of visitors. However, if gatherings took place only in the summer, housing needs would be less substantial.

Recent archaeological work provides more insight into ritual gatherings at Shell Mound than it does the details of everyday living. Still, evidence for habitation at Shell Mound is found in an array of postholes and other features typical of the domestic needs of housing, meal preparation, and family care. Current evidence does not allow accurate estimates of the resident population or of the size, shape, and spacing of their houses. When not hosting gatherings, the population of Shell Mound was likely modest in size, perhaps fewer than 100 people. Hundreds more would gather periodically for communal rituals that left a more conspicuous mark in the archaeological record. If you are visiting Shell Mound on a hot summer day, you may be enjoying a refreshing breeze from this location on top of the mound. Or, if you are visiting Shell Mound on a blustery winter day, you may have noticed the stillness and warmth of the air down in the enclosed area behind you. Archaeologists suspect that Shell Mound residents shifted the locations of their houses and related activities with the seasons. Open-sided shelters like Seminole chickees would have served the needs of warm-weather structures along the ridge top, while walled houses in the enclosed area would have been preferred for cold and stormy weather. Other housing arrangements may have been needed to accommodate large groups of visitors. However, if gatherings took place only in the summer, housing needs would be less substantial.

Mariculture

Oysters were managed by Native people for long-term sustainability. Excavation at this location provided clues to two forms of oyster mariculture that are still practiced today.

Culling. Oyster clusters were culled by removing mature individuals, leaving smaller ones behind to grow. The holes of boring sponges–parasites that drill into oysters for shelter–are evidence of this practice. Returning separated oyster clusters to the water leaves attachment scars vulnerable to boring sponges.

Shelling.The right valve (shell) of oysters—the “lid” you remove to get to the edible part—was returned to the water to encourage the growth of reefs by providing substrate for spat (baby oysters) to settle and grow. The left valve was added to the growing mound as construction material. Archaeologists discovered evidence for early peoples’ shelling practice by counting the valves in representative samples of Shell Mound’s

layers and noting the predominance of left over right valves during the period of time when local reefs were being intensively harvested.

More information about oyster mariculture at Shell Mound.

Oysters were managed by Native people for long-term sustainability. Excavation at this location provided clues to two forms of oyster mariculture that are still practiced today.

Culling. Oyster clusters were culled by removing mature individuals, leaving smaller ones behind to grow. The holes of boring sponges–parasites that drill into oysters for shelter–are evidence of this practice. Returning separated oyster clusters to the water leaves attachment scars vulnerable to boring sponges.

Shelling.The right valve (shell) of oysters—the “lid” you remove to get to the edible part—was returned to the water to encourage the growth of reefs by providing substrate for spat (baby oysters) to settle and grow. The left valve was added to the growing mound as construction material. Archaeologists discovered evidence for early peoples’ shelling practice by counting the valves in representative samples of Shell Mound’s

layers and noting the predominance of left over right valves during the period of time when local reefs were being intensively harvested.

More information about oyster mariculture at Shell Mound.

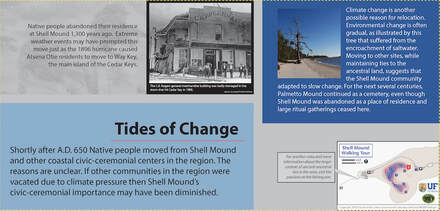

Tides of Change

Shortly after A.D. 650 Native people moved from Shell Mound and other coastal civic-ceremonial centers in the region. The reasons are unclear. If other communities in the region were vacated due to climate pressure then Shell Mound’s civic-ceremonial importance may have been diminished.

Climate change is another possible reason for relocation. Environmental change is often gradual, as illustrated by this tree that suffered from the encroachment of saltwater. Moving to other sites, while maintaining ties to the ancestral land, suggests that the Shell Mound community adapted to slow change. For the next several centuries, Palmetto Mound continued as a cemetery, even though Shell Mound was abandoned as a place of residence and large ritual gatherings ceased here.

Shortly after A.D. 650 Native people moved from Shell Mound and other coastal civic-ceremonial centers in the region. The reasons are unclear. If other communities in the region were vacated due to climate pressure then Shell Mound’s civic-ceremonial importance may have been diminished.

Climate change is another possible reason for relocation. Environmental change is often gradual, as illustrated by this tree that suffered from the encroachment of saltwater. Moving to other sites, while maintaining ties to the ancestral land, suggests that the Shell Mound community adapted to slow change. For the next several centuries, Palmetto Mound continued as a cemetery, even though Shell Mound was abandoned as a place of residence and large ritual gatherings ceased here.

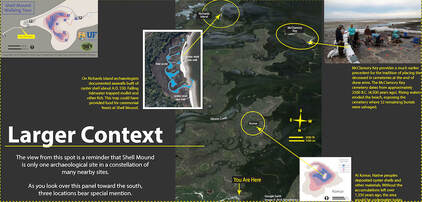

Larger Context

Shell Mound is only one archaeological site in a constellation of many nearby sites. Three locations bear special mention.

Richards Island- On Richards Island archaeologists documented seawalls built of oyster shell about A.D. 550. Falling tidewater trapped mullet and other fish. This trap could have provided food for ceremonial feasts at Shell Mound.

McClamory Key- McClamory Key provides a much earlier precedent for the tradition of placing the deceased in cemeteries at the end of dune arms. The McClamory Key cemetery dates from approximately 2500 B.C. 4,500 years ago). Rising waters eroded the beach, exposing the cemetery where 32 remaining burials were salvaged.

Komar- At Komar, Native peoples deposited oyster shells and other materials. Without the accumulations left over 1,350 years ago, the area would be underwater today.

Shell Mound is only one archaeological site in a constellation of many nearby sites. Three locations bear special mention.

Richards Island- On Richards Island archaeologists documented seawalls built of oyster shell about A.D. 550. Falling tidewater trapped mullet and other fish. This trap could have provided food for ceremonial feasts at Shell Mound.

McClamory Key- McClamory Key provides a much earlier precedent for the tradition of placing the deceased in cemeteries at the end of dune arms. The McClamory Key cemetery dates from approximately 2500 B.C. 4,500 years ago). Rising waters eroded the beach, exposing the cemetery where 32 remaining burials were salvaged.

Komar- At Komar, Native peoples deposited oyster shells and other materials. Without the accumulations left over 1,350 years ago, the area would be underwater today.

More information about the archaeological investigations at Shell Mound from the Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology, Department of Anthropology at the University of Florida

"Solstice Feasts and Other Gatherings" by Ken Sassaman in Adventures in Florida Archaeology, the magazine of the Florida Historical Society

- Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey

- Survey 2013-2014 (LSA Technical Report 21)

- Survey 2014-2016 (LSA Technical Report 25)

- Summer Solstice Feasts

- Oyster Mariculture

- Palmetto Mound

"Solstice Feasts and Other Gatherings" by Ken Sassaman in Adventures in Florida Archaeology, the magazine of the Florida Historical Society

Past Friends' Solstice Gathering Reports

- 12/21/2023 Winter Solstice in Cedar Key

- 6/24/2023 Summer Solstice 2023

- 12/21/2023 Winter Solstice Without Rain

- 12/23/2021 Winter Solstice's Blustery Tradition

- 6/21/2021 Summer Solstice Success

- 6/21/2019 Summer Solstice at Shell Mound

- 12/23/2019 Solstice Gathering a Near Washout

- 12/21/2018 Stormy Winter Solstice

- 12/21/2017 Winter Solstice at Shell Mound